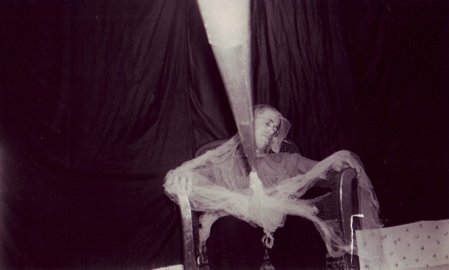

Trumpet Mediums

When I first scanned this photograph at the Rhine Research Center I had no idea what was going on in the picture (aside from all the ectoplasm). I found out a day or two later. This guy is what’s called a “trumpet medium.” The dead spoke via a trumpet. A trumpet. Wait, is there there some sort of religious significance here? Anyway, at one time there were a bunch of mediums call trumpet mediums. (It’s just a little phallic too, isn’t it?) This particular trumpet medium is Ed Moore.