For the past month, I’ve been working for the United States Census and as you might have read, there’s been some some resistance to filling out the questionnaire. I had the opposite response. I wished the questionnaire was even longer than the long form of 2000. For the past twenty years I’ve been digging through old records, including old Census records. I can’t get enough data. During our Census training they tried to communicate this idea: everyone deserves to be counted. But for me the point is: no one should be forgotten.

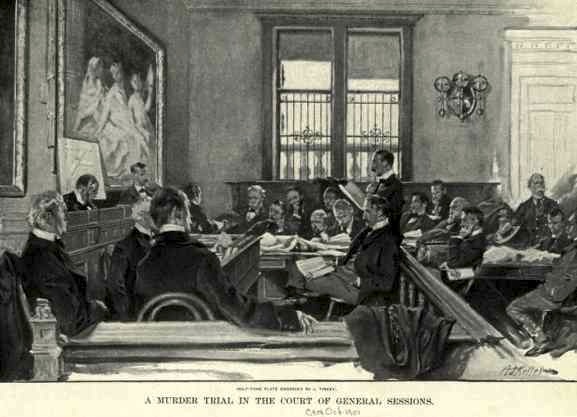

For instance, last year I was at the Municipal Archives, where the records for the government of New York City are stored, looking through old indictment records for the Court of General Sessions. From 1790 to 1962, General Sessions was the criminal court where the city’s felony cases were heard. Going through these records you really get the sense that some people are totally gypped by life.

This was especially true in 1892, the year I picked to explore. Times were hard and on a busy day at the court a new prisoner was hauled up in front of the judge every fifteen minutes. I started to think of the place as The Conveyor Belt of Sorrow.

1892 was the kind of year where it was actually worth it to the City to indict one poor slob for “receiving stolen goods,” a felony charge, when the stolen goods in this particular case were nothing more than a measly 14 bunches of bananas. Another guy was arrested for stealing a blanket off a horse. The guy was just trying to stay warm. The banana man and the blanket guy would have been placed in a pen alongside murderers and rapists, all waiting to see what blow life would strike next.

It was a such short fall to rock bottom. On September 16 a man named Andrew Stewart decided to cut to the chase. As workmen on their lunch break watched, Stewart jumped from the relatively new Washington Heights Bridge and into the dark brown Harlem River below. When a workman rushed over and pulled him out, Stewart said he took the dive because he was unable support his wife and children, and he couldn’t bear to see them suffer any longer. They threw him in jail.

117 years later, long after Andrew and his wife and children lived out their lives as best they could and died, here I was, sitting safely inside the Municipal Archives getting my hands dirty handling their indictments and others, all covered with the accumulated dust and grime of over a century’s worth of pain. “Where are your gloves?” the director asked me as she walked by. She returned a minute later with a box-full and I reluctantly pulled on a pair. I don’t mind the dirt, and it felt like handling the paper directly brought me somehow closer to the past. But the gloves aren’t only for me, they’re also to preserve the increasingly fragile documents I held in my hands, the very papers where the court said I don’t care how hungry you are, to the banana man or how cold you are, to the horse blanket man, and indicted them.

What does a years worth of the worst crimes in New York City look like in 1892? Most of the indictments were for burglary, larceny and assault. There were also: 37 cases of abduction, 36 rapes, 24 murders, 18 cases of manslaughter, 8 suicide attempts, 7 cases of sodomy, 6 for adulterated milk (the cause of thousands of infant deaths yearly), 3 seductions, 1 case of cruelty to children, and 97 indictments for prostitution, which was then called colorful names like, “Keeping a House of Ill Fame.” When two men had sex with each other they were charged with “Crimes Against Nature.” There were 11 indictments for crimes against nature that year.

After a while, the courthouse parade of transgressions that humans inflict on each other started to appear to me almost routine. But not any less pitiable. I was continually drawn to the attempted suicides. 29 year old Annie Rogers was picked up for intoxication, but indicted for trying to hang herself in her jail cell. When her turn came to be brought out of the pen and up before the judge, her defense was she was “sick and destitute.” That’s why she was drinking in the first place, she explained. Joseph Dietze, a 19 year old from Germany who had no place to live, shot himself in Central Park. “I die for my love” he told the officer who found him. Vitimise Daloni, 52 years old, tried to end it all with a “solution of water and sulphur from matches.” Could that have possibly worked? George Hawthorn, a 34 year old unemployed bartender, seemed more determined. He swallowed Paris Green, an insecticide that was so toxic it sometimes burned the trees and grass where it was spread.

Included with the indictments are records of people begging for mercy. One boy who was arrested for Crimes Against Nature wrote the judge that he, “never was arested [sic] in my life before for any offence [sic] of any kind and will [you] please look into my case and for god sake be merciful with me for I am now a physical wreck … I am young yet and hope when I come out of Prison I will be a better man.” The fact that he respectfully capitalized the word prison only made him seem that much more vulnerable. It was a sad show of deference for the very thing that almost certainly would not make him a better man.

The court and New York City were also struggling with what to do about the most vulnerable of the poor in the nineteenth century—children.

On April 14, Minnie Marquies was brought in for starving her three children, Joseph, Harry and Dolly, “so called although a boy” the indictment read.

A Census worker had returned to her basement apartment one night after knocking and receiving no answer during the day. Inside a room “super-heated by a roaring stove,” he found three naked and extremely weak and emaciated children, aged five, three, and eighteen months.

In court, a sorry cycle of abuse came out. Minnie told the judge that she was French, 18 years old, and that she was 13 when she married her first husband Joseph Marquies, who shot himself the day before their son was born. But a representative from the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children who had dealings with the family before told the court a different story. Years before, Minnie’s mother Catherine had been mistreating Minnie and her sisters Cecilla and “another daughter who was early put out to service.” The Society had gotten involved when Catherine’s second husband assaulted the then nine year old Cecilla. The husband was packed off to Sing Sing and Cecilla was sent to the Convent of the Sisters of St. Dominick. (They didn’t say what they did for Minnie, who was really 22 and Irish, or her unnamed sister.)

This time, the now grown Minnie was indicted and her children were taken away from her and sent to Presbyterian Hospital. The story provided by the indictment ends there. A newspaper account gave a brief update on Minnie’s children. Harry was expected to survive, Dolly was not, and Joseph had already been placed in an orphanage. (You could say that the Census worker saved Harry and Joseph’s lives.) I learned from the 1880 Federal Census that Minnie’s unnamed sister who was prostituted in order to support the family was named Sarah, and that Minnie had been “lame since birth.” (A rare and poignant notation that had been made by the Census worker and one that would never be made today.)

Except for Joseph, after Minnie’s court appearance the family disappears completely from the public record. But Joseph shows up one more time in the 1900 Federal Census, when he was 13, in Sister Agatha’s Home for Children in Rockland County, along with with 558 other “inmates,” thirty-six teachers, nine servants, eight laborers, three seamstresses, two bakers, and one laundress, fireman, watchman, blacksmith, engineer, bricklayer, carpenter, gardener, shoemaker, and chaplain. After that Joseph disappears forever, too.

After spending a couple of weeks reading indictments the case I kept coming back to was the very first one I read.

On April 4, 1892, Antonio Aragona was indicted for “Abduction.” He’d been working as a barber in the basement of 352 Third Avenue on June 1, 1891, and was out on the sidewalk taking a break when fifteen year old Mollie Ogler walked by. According to the Police Court records, Aragona invited Mollie into the basement, took her to a back room, placed her on a bed and then told her to take down her drawers. Mollie obeyed and in Aragona’s own words, he “did bad things.”

But the indictment was from 1892. Why did Mollie’s mother Henrietta wait almost a year to complain and have him arrested? Here’s what I found.

Two months before having Aragona arrested, Henrietta took her daughter to the New York Infant Asylum. Mollie was pregnant. The New York Infant Asylum had been established at the time to help with the abandoned infant problem and it was hoped that it would be an improvement over previous alternatives like Blackwell’s Island Almshouse, where infant mortality rates approached 100 per cent. A physician once wrote about Blackwell’s that, “It would be an act of humanity if each foundling were given a fatal dose of opium upon its arrival.” At the Infant Asylum an unwed and indigent pregnant woman would receive care and her infant a home, but it was a facility a woman could use only once. Once was a mistake, twice apparently was a life style, and those women and their babies were not welcome.

On the first of March, Mollie gave birth to a son. She never even gave him a name. He lived for two hours and died at 5pm. On the death certificate the cause of death for “male Ogler” was listed as “premature,” and his age was put at six and a half months. This means he was conceived sometime in mid-August.

Even given the fact that his age was an estimate, it’s unlikely that he could have been the product of a June 1st rape. Perhaps Henrietta was just looking for help, or retribution, and since Aragona admitted to doing bad things to Mollie she might have figured he was as good a place to start as any.

But on May 18th, the Assistant District Attorney hand wrote the following note on the front of the indictment:

“The girl charged to have been assaulted in this case is without doubt [an] imbecile [the term then used for those with developmental disabilities]. I have attempted to get from her a statement of the circumstances of the alleged assault, but she is unable to answer my questions rationally. I am quite sure that no conviction could be had in this case — moreover, Mr. Stocking [the assistant superintendent of the Society For the Prevention of Cruelty to Children] has told me that his society had no confidence in the case that declined to [illegible] it. I recommend the dismissal of this indictment.”

In the end it didn’t matter what they decided to do. By the time the DA made that notation Henrietta and Mollie had already disappeared. When the District Attorney’s subpoena server showed up at their apartment at First Avenue, he was told that Henrietta and Mollie had moved to 246 East 10th Street. At 10th street no one had ever heard of them. He canvassed the entire neighborhood but no one could tell him anything. He ended his report admitting that he “was unable to gain any information in regard to the whereabouts of the above named persons.” They where gone.

I spent a few hours at Cornell’s Medical Center Archives where the records for the New York Infant Asylum are stored, searching for a clue about what might have happened to them. The annual reports gave glimpses into what life was like at the Asylum, and it does sound like it was significantly better than Blackwell’s.

Every donation at Christmas in 1892 was listed for instance, and among the lists of toys and clothes and money I found, “1 very large turkey, 1 barrel apples, 10 pounds candy, 100 oranges, 100 lemons, bananas” from Mrs. Henry Knickerbacker, who 30 years later would demonstrate that you don’t have to be destitute to be desperate. While eight servants were standing by awaiting word for dinner to begin, she leapt from her Central Park West apartment to her death. She was 84.

Mollie’s single page patient record was among the archives, carefully preserved. It was so brown, brittle and flaking I was afraid to even pick it up. Instead I stood up, looked down and read. I had to sign a form saying that I would not reveal anything personal I learned about the patient Mollie, but there was almost nothing personal in her record in any case, and nothing that told me anything about who she was or where she finally ended up. There was an odd note about her parents however, who were not patients. “Parents of mother both very short.” Why include that fact? They must have been seriously short for someone to think it was worth noting.

Henrietta and Mollie (whose real name was Mary, I learned from various sources, Mollie was a nickname) show up in the public record one more time, eight years later, in the 1900 Federal Census. They hadn’t gone far. They were now living at 217 First Avenue, twelve blocks down from where they were in 1892. In this Census Henrietta is four years older than the age she told the court, but it’s not unusual for a woman to lie about her age. Except Mollie is now three years younger and that can’t be right. While it’s technically possible that Mollie gave birth at 12, it’s not likely that Henrietta would have lost the opportunity to show the court how young her daughter truly was, making the crime of having sex with an underage mentally challenged child that much more indefensible. More likely Henrietta, who was now telling the truth about her own age, had taken to lying about Mollie’s, because Mollie could still potentially benefit from having a few years shaved off.

I wasn’t able to find out what happened to them in the end. There are no death records. I like to think they got away. That they left New York, changed their names and lived out their lives some place where it was safe and green and quiet and where they never had to beg anyone for mercy again. If Mollie lived to a ripe old age, there’s a chance that she and I were both alive at the same time. It’s so strange to think that I was on the earth at the same time as someone who lived through that dark time, who would have strolled these same streets as I do now except in long dresses, past gas lamps, horses and wild pigs.

However, I think I know how Mollie and her mother really ended up. Mollie died first. Hopefully. Because without her mother to take care of her, her ending, which was likely sad, would only have been that much worse. Henrietta probably couldn’t afford to bury Mollie so I think she might have left her wherever she laid and moved on, knowing that the city would take care of her final arrangements. In New York City, all unclaimed bodies and the destitute end up in trenches on Hart Island, the City’s Potter’s Field, where it is surprisingly lovely, green and protected. It’s like the country out there. You can see and smell the Long Island Sound, and the wind and the earth. And where the graves lie, it feels peaceful.

I researched and visited Hart Island when I was working on Waiting For My Cats to Die, and I know that on Hart Island Mollie would have finally been treated well. The people responsible for the burials there are prison inmates, and knowing that they themselves might end up buried there some day, they would have interred her tenderly, as if she were their own daughter.

When Henrietta died there may have been no one left to take care of her final arrangements either, so she would have been reunited with her daughter on Hart Island, buried under the name “Jane Doe,” as all unidentified females there are called. If they’re both there, without any idea of when they died it would be impossible to figure out which, of all the hundreds of thousands Jane Does buried there over the past one hundred years, Henrietta and Mollie might be.

Here’s why I love the Census and other documents that are saved and maintained. Whoever heard of poor Mollie Ogler? Some miserable creep took advantage of her 100 years ago, he got away with it, and anyone who ever knew her or cared is long gone. Doesn’t she deserve to be remembered? If you’re a famous person, people are going to write books about you, and articles, and there will be a lot for historians to recover hundreds of years later.

But if you’re poor and destitute, without records like the Census and others, there’s a good chance you’re going to disappear entirely. It will be like you never existed.

There are 534 boxes of General Sessions records at the Municipal Archives and they are available to any researcher. You can also find birth, death, and marriage certificates there, as well as the Census and many other historical records like the records for burials on Hart Island. Likewise, the Cornell’s Medical Center Archives are also available to any researcher and they have records for many other medical institutions. And finally, the federal Census records are also available tons of places and online at sites like Ancestry.com.

Wow, fascinating stuff! I agree, nobody should be forgotten and thank you for sharing Mollie’s story. I, also, wish that there was more information requested by the census takers and I was surprised this year how little was asked on the form. I’ve been able to piece together things about my ancestors that not even my oldest living relatives knew through past census information. I can understand some people’s fear of government but the census is a treasure trove for researchers. Thank you for connecting the dots in Mollie’s sad, but very human story. She is now remembered! You are an amazing researcher.

Plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose.

“parents of mother both very short” – could it mean short as in abrupt (in temperament or speech), rather than stature? People were shorter then anyway, so how much shorter would “very short” have been before being called “midgets” – what they now call “little people”.

Wonderful stuff. We need more history of ordinary people.

Fascinating research, and interesting in the grim lives of poor people back then.

I think archives are also a great treasure-trove for historians, researchers, etc. I have, at various times, had possession of civil war letters (handed down by grandparents) and donated those to the state historical archives. I also have several significant historic documents (gift from a distant cousin who is history professor) and plan to leave those to state archives as well.

Preserving those within a family might be fine for some people; I just think they should be made available to scholars/historians/researchers instead of languishing in some dusty attice somewhere.

Oh wow, what did the Civil War letters say??

I mean to say, the only things I know about my great grandparents I got from the census. My parents couldn’t tell me much about them!

Hey Stacy,

Most of the letters were personal, telling about injuries, losses, suffering and asking about those back home. The main significance I realized was that a few mentioned specific battle sites and the weather, the win/loss and grim stuff like whether they had anything to eat or not. When I read the book, then saw the movie, “Cold Mountain” it reminded me alot of the awful conditions some suffered — and also the terrible “Home Guards” who were mostly just thugs who scared the locals while other men were off fighting in the war. I did make copies, but thought the originals would be better perserved in the archives.

I have a written detailed, lengthy genealogy of my paternal ancestors and I listened to ‘stories’ of long-ago relatives at my grandparent’s fireside. I guess, as a result, I never had much curiosity about ancestors, but do think had it not been for that open sharing from them, I’d have been eager to research and learn about my ancestors. Many of my relatives are buried in cemeteries around this area, and it’s sort of a local joke that everyone is related as very distant cousins in one way or another. Such is the small town southern life!

Oh man, those letters sound amazing. I’d like to read them. You should post them! I wish my grandparents had been more talkative and me more interested at the time.