Last night I was watching a Livestream of the demonstration here in response to George Zimmerman’s not-guilty verdict. There were two simultaneous chat streams, one civil, and the other ugly and racist. I went back and forth reading the two entirely different takes on what had happened the night Trayvon Martin was killed, and what was happening last night. I can see how reasonable people disagree, but at least one side was not reasonable. They might say the other side wasn’t either.

It reminded of the trouble I had researching one of the darker chapters in my book. There was a riot in the Chatham Street Chapel in downtown New York on July 7, 1834. A mostly black congregation had originally gathered in the chapel on July 4th to celebrate Emancipation Day, the day when slavery was outlawed in New York in 1827. But a mob had interrupted and prevented their service and they had reconvened on the 7th. There was a misunderstanding about who had the space for the night and a riot ensued.

I tell the whole story in my book, but what I want to talk about was my challenge in figuring out what had happened that night. Every newspaper account I read depended on the paper’s stand on abolition. If they were anti-abolition, the blacks were the aggressors, if they were for the abolition of slavery the white mob had started it.

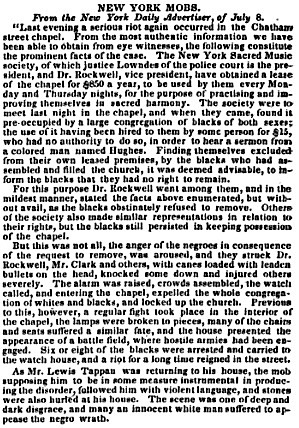

Here is an anti-abolition account. (Sorry for the tiny print.) It’s insane because even though they get some of the facts right, that the blacks had arranged and paid for the use of the space, well, you’ll see. The “colored man named Hughes,” identified as if he was some insignificant personage, was Benjamin F. Hughes, the principal of African Free School No. 3.

The only people arrested that night were four young black men. Thanks to the amazing Municipal Archives I was able to find the original arrest records—this is particularly astounding since this was before we had the official New York Police Department we have today—and the names of the young men who were arrested.

Even more astounding, one of the men arrested, Samuel R. Ward, was so upset at the injustice of what had happened, he immediately set about educating himself and he spent the rest of his life lecturing around the country against slavery (sometimes with Frederick Douglass). And he wrote about the events of that night much later in his life, when he retired. There’s even a note of humor in his account, when he points out that the only person who suffered a true physical injury that night was the white man in charge of the mob, who hurt himself jumping out a window fleeing from what he had started.

I wasn’t there the night Trayvon Martin was killed, and neither were any of the people talking about it last night. And all the witnesses to the riot on July 7, 1834 are long dead. In my book I wrote down the three versions I found and left it to the reader to decide. But it’s clear where I stand. If there were a trial today I’d go with Samuel R. Ward’s version.

The Chatham Street Chapel was torn down and on the site today is, of all things, a prison. I was not allowed to walk up and take a picture of the plaque commemorating the site of the Chapel. So I went up to the plaza in front of One Police Plaza, walked past the benches and hedges, leaned over and took this shot.

Side note: the guards who wouldn’t let me walk over and take the picture insisted that they’d worked there for decades and there wasn’t a plaque anywhere about any chapel.

Wow, absolutely fascinating, particularly the part about Samuel Ward. Guess I can’t put off buying a copy of this book any longer. Lewis Tappan was the abolitionist instrumental in working for the freedom of the enslaved people on the Amistad, assuming it’s the same person. Can’t quite figure out (from reading this article) how he fit into this story–would seem an odd person to be victim of “mob.”

He spoke at the service that was mobbed. He wasn’t behind anything though, and this article neglects to mention that the mob broke into house, threw all his furniture out on the street, including a piano if I’m remembering correctly, and then they burned everything.

The line about the innocent whites suffering to appease the “negro wrath” just kills me. The whites were the wrathful ones and the blacks were the ones who suffered, and if anyone deserved to be mad it was the blacks.

Also it’s sad because it reflects an attitude that endures today.